Marc Brownstein, the bass player for The Disco Biscuits, co-founded HeadCount with Andy Bernstein in 2004. The organization aims to translate the power of music into action, largely by registering young people to vote. The nonpartisan group has registered more than 350,000 people so far.

Our G.W. Miller III spoke with Brownstein, the son of a career politician, about the the importance of voting. Images by Chip Frenette.

How did you start HeadCount?

The executive director of HeadCount, Andy Bernstein, was my co-founder. It really just started out of a series of conversations that were a result of feelings of frustration about the lack of engagement and the apathy that we would experience in the music world. And we felt like the power of music, and the power of the fan bases that we had in front of us, and the enormous reach that my band – and a couple of the bands that we were friends with, we felt like we could potentially reach hundreds of thousands, if not millions of kids with a simple message, which was to let their voice be heard.

Were there other people doing similar things at the time?

There were all these protest movements of the 60s that were very closely tied with the musical world, the world of artists and entertainers. John Lennon is a perfect example of a protest artist and there were so many others.

Through the 80s and 90s, there was complacency or general apathy. People used the musical events they were going to as an escape from the real world. That’s the way it was for me when I was going to see music in the90s. There wasn’t really a political tie-in. Occasionally you’d run into the Greenpeace table or the WaterWheel table or other environmental groups that were out there trying to enact social change.

In terms of the political stuff, there wasn’t anybody really out there on the ground, in the field trying to engage people. We were told that Rock The Vote had sort of backed off their field strategy and shifted to an online strategy. Some of the core bands that we were working with told us that there was a real need for what we were doing.

We thought to ourselves: What can we do? How can we engage people? How can we do it in a nonpartisan way that is not going to be divisive and rather, inclusive?

In order to unite people, your platform needs to be nonpartisan, especially in the music world, where you can’t just assume everybody is from one party or the other. There are huge gradations of people that are extremely, extremely diverse geographically and politically.

After consulting with the guys in the Grateful Dead and the Dave Matthews Band and Phish, we agreed that there was a real need for a field team of volunteers registering voters.

What does this look like at shows?

It looks amazing. It’s such a source of pride for me. I went to see Phish at the Mann Center and there was a HeadCount table set up there. I went to see the Dead and Company a few weeks earlier. HeadCount along with Reverb is running Participation Row, which is the nonprofit village of Grateful Dead related charities. They all work together. It’s this gorgeous group or red tents. And this is across the country.

We’re at thousands and thousands of events, regular rock concerts and festivals all over the country. We have days when a thousand people are registered in Tennessee and a thousand people were registered in New York and you start to see the aggregate of the work of actual people with clipboards in the field. It’s incredible.

The volunteers are the backbone of this organization. We’ve had 15,000 different people volunteer for us over the years. Right now, we have 10,000 volunteers working thousands of events across the country.

Right now, we’re over 350,000 registrations.

Are you talking about people going to certain shows, which means you’d likely get people registering a certain way?

We are operating throughout all the different genres of music. We’re targeting music fans.

The Disco Biscuits are a jam band. We started with The Disco Biscuits and moe. and the Dead, Phish, Dave Matthews Band. Theses were our first bands. But we grew out of the jam band scene. Eddie Vedder has been a huge supporter. He’s gotten on stage and talked specifically about HeadCount and how important it is to vote and get involved.

If you go onto HeadCount.org, you’ll see how diverse the list of artists is that we’re working with at this point. From Pearl Jam to the Dead to Jay Z and Beyonce.

Your board of directors is an impressive list of music All-Stars.

These are some of the smartest people in the entire music industry and some of the people are also involved in politics.

Like Pete Rouse?

Pete was the White House chief of staff during the Obama administration. You don’t get much higher than chief of staff in terms of influence in Washington and otherwise.

Having guys like that on the team is incredible and they have been really engaged. What we have is an incredible collection of minds. When we have our board meetings, it becomes a think tank on social progress and social engagement. When you have some of the greatest minds in music and politics come together, great things tend to happen.

During the election cycle, we are entirely focused on the election. It’s all about registering voters and getting them out to vote from now until election day. But from then until the mid-terms, there’s time to breath and use the infrastructure to work on other initiatives.

Do you think people are more politically aware or active, or more engaged in what’s happening in the public space?

Right now is a particularly trying time politically. You have more people engaged in the process because this election has become somewhat of a circus, especially this primary season. People are keenly aware of what’s going on but that doesn’t always necessarily translate into people voting.

At the same time, as people are engaged, there’s an incredible amount of apathy. And that’s not from people who don’t know what’s going on. That’s from people who are really intelligent who have great explanations for why they don’t feel represented in the system right now.

At some point in the near future, one of the things that will reach a tipping point is money in politics. People feel like politicians are representing the interests that are funding their reelection campaigns. I don’t know what the solution is. Term limits? That might be a great idea actually. Allow people to make the best decisions possible rather than just gridlocking Washington.

There are a lot of great, nonpartisan issues coming up right now. People agree overwhelmingly that cannabis should be legalized for medical use. People agree overwhelmingly that money should be taken out of politics.

You believe in the system but you think we need people who are more engaged in the actual practices of the system? The system doesn’t need to be thrown out all together?

I mean, 72.6 percent of all people who are eligible to vote in this country did not vote in the primaries. Only 7.3 of the country voted for Hillary; 5.9 percent of the people voted for Trump; 5.3 percent of the people voted for Bernie Sanders; 4 percent voted for Ted Cruz; and about 4 percent voted for everyone else combined.

I had a friend who just yesterday was telling me, “I’m so upset about the state of affairs in politics right now.” I said, “Why don’t you tell me what’s bothering you?” And he said, “I hate both of the candidates running for president.” I said, “Oh, really, who did you vote for in the primary?” He looked at said, “Well, I didn’t vote in the primary.” I said, “I’m not sure this conversation is going the way that it needs to going right now.”

Who represents you and your beliefs the best of all the candidates? Did you research them? Why the hell didn’t you go and vote for that person? I can’t fathom that somebody who cares about politics decided to sit out.

There’s also the option to go into the booth and select neither. Just vote on the down ballot candidates. Vote on the local stuff, the ballot initiatives and issues.

People feel disenfranchised from the system. They feel like they are not represented. But then they agree that pot should be recreationally legal everywhere, as it is in Oregon, Washington state and Colorado. That was voted as ballot initiatives in those states.

People say the system is rigged and that nobody represents their interests. Ok, that may actually even be true. Obviously, the representatives try to redraw district lines to line up with the demographics of their party so they become reelected. In that way, the system is rigged. But there are valuable social issues that are on down ballots, like same-sex marriage, things that people legitimately care about but they haven’t realized that these are things they could go and vote on.

Voting does matter. You do get to shape the world around you in a lot of states.

Do you see a future in politics? Or is this your way of making change and getting involved?

I just started the process of finishing college. I left in my senior year to pursue a career in music.

My father was a career politician. He was elected 17 out of 18 elections that he was in. He was the youngest member of the New York State Assembly in the history of New York state. He was elected when he was 26 years-old. He made his way all the way up to state Supreme Court judge and he served on the appellate division as well. He ran for chief judge of New York state, lost that election and went back to the private sector.

I don’t think that I have the stomach for politics. But I would be lying if I said that I look at some of the people who run and win and I think to myself, “This is ridiculous that these people are running and winning. There have got to be better people out there.”

The bottom line is that I think that I have my voice here. What we have done has made enough progress in the 12 years that we’ve been doing it that if we stick with it and really put our noses to the grindstone, hopefully, we’ll be able to engage millions of people into the political process. That’s the ultimate goal.

Editor’s note: This is the full interview with Marc Brownstein. An edited version appeared in the summer issue of JUMP.

Fake Boyfriend: Celebrating Each Other’s Weirdnesses.

Text by Morgan James. Images by Rachel Del Sordo.

It’s an uncharacteristically cool summer evening but the energy inside of Milkboy Philly is kinetic. The ladies of Fake Boyfriend are hurriedly arriving to soundcheck before their show. Cars are double parked out front. Everyone is frazzled. Everything is fun.

Ashley Tryba, 24, Sarah Myers, 23, and Abi Reimold, 24, are all huddled in the back service stairwell of the upstairs chuckling at the absurdity of their current state and location whilst completely comfortable existing in that space.

When asked what excites them about this summer, Myers exclaims, “I’m fucking stoked to move into our new house together.”

“We’re moving into a bigger, better, more awesome house just further west of where we live now,” Tryba continues. “We live in West Philly.”

“Does it explain a lot?” Reimold chimes in and laughs. “It explains us.”

It does. Though these Temple grads are all from the suburbs of Philadelphia, everything about these three emanates an inviting, quirky, punky and vulnerable realness – the same kind of realness one finds in abundance on any stroll down Baltimore Avenue.

Fake Boyfriend’s debut EP, Mercy, is a 4-track manifestation of their convivial duality.

The project begins with “Ship,” a writhing and aggressive ode to new wave. It’s in-your-face. You can’t help but join their charge even if you’re unsure of the feelings percolating within.

“I think the rawness of the instruments and the punkiness of the instruments largely stems from the fact that we’ve never played instruments before,” says Myers. “And for me personally, I’ve always drawn a lot of power from punk music.”

Jake Ewald, of Modern Baseball fame who also produced Mercy, lauds the band’s rawness along with its versatility.

“There was no stiffness in regard to making a certain song sound like a punk song, or making a certain song sound like a Sharon Van Etten song, or anything like that,” he says. “Everything they wrote was super organic, and their group writing dynamic was really helpful.”

Punk à la Hole and Glenn Danzig circa The Misfits are inspirations of Tryba as well.

Amazingly, Reimold is the only longtime instrumentalist, having played guitar and writing songs since she was 12. She learned how to play the drums for this band.

Both Tryba and Myers learned guitar and bass, respectively, within the past several years, though Tryba’s foray into music took some sisterly encouragement from Reimold.

“I was hesitant to start the music project because I didn’t have confidence that I could learn how to play guitar,” Tryba says. “I just saw it as a big hurdle. And Abi lent me her guitar and amp and basically threw it in my hands.”

Tryba, ostensibly the biggest personality of the three, has few inhibitions about expressing her insecurities, though that wasn’t always the case.

“One of the reasons I was really insecure about playing music and didn’t have confidence in myself enough to start was because an ex-boyfriend of mine had told me he wouldn’t want to make music with me,” she reminisces, “even though he liked my voice and thought that I had a good opinion about music, because ‘girls being in bands was gimmicky.’”

Ewald notes Fake Boyfriend’s nascent musical beginnings but views it as a positive quality more than anything.

“Ashley, Sarah and Abi created a really cool musical aesthetic for the EP,” he says. “Since they were all working with instruments they hadn’t spent too much time with, the parts they wrote were entirely uninhibited and they came out super cool.”

This rawness can be felt heavily in that snarling 27-second demo dubbed “Gimmick” on their Bandcamp. Its inspiration? One can thank the misguided perceptions of an ex-boyfriend for that.

The cheeky band name? Fans can also thank an ex-SortaBoyfriendButNotReally for that.

“It’s just kind of playful,” Tryba explains. “It also describes someone who you’d be dating for three months. And you maybe met their parents and they met yours. And you’re making dinner together and then all of sudden they just like… ghost.”

But the reality is that Mercy is not about significant others, nor relationships. It’s about navigating the crosshairs of who you want to be.

“A lot of times the relationship lens is really just a lens into the turmoil of growing up,” Myers expounds. “When you’re in a relationship you learn a lot about yourself. You process a lot of your huge life jumps like how you empathize with people, your emotional intelligence…. learning how to be someone who is kind and good to other people, but also having to unlearn a lot of the bullshit people have put inside and taught me and told me to hate about myself.”

“And a lot of it for me,” says Tryba, “Mercy was dealing with this paradox that was me coming into myself as a person. Since I was young I was kind of confused about my identity – whether I wanted to be scary or pretty? One year I was a scary princess for Halloween. And I feel like that’s how I describe our sound too. We don’t have to pick being femme or butch or tough or soft. We can be whatever we need to be to process our emotions in this way… to voice ourselves in this way.”

“Gritty and pretty,” Reimold chimes in.

Tryba describes the angriness in the sound as a response to the violence against women, against underprivileged populations and the frustration of self-perceived limitations as a result of what other people have said or done to you.

“And then the pretty or sad parts are kind of the sounds of young adult depression,” she laughs.

Mercy takes listeners on a journey that is their journey but also the journey of many 20-somethings coming of age in this world. A world that Fake Boyfriend, despite the gravity of their music, tries not to take too seriously.

“It’s just such a dark world,” says Reimold. “It’s sad. You can focus on that or you can make your friends laugh. We’re just here to celebrate each other’s weirdnesses and enjoy them and take pleasure in them.”

PJ Bond: Redefining Success.

PJ Bond toured the world as a solo artist and with various projects for many years. And then he gave all that up.

Now, he works at American Sardine Bar.

And he couldn’t be happier.

Images by Natalie Piserchio.

I make sure the glasses are clean. At least, that is what I tell people now when they ask what I do. These days, I work behind a bar but that’s fairly new for me. For the better part of 15 years, you’d have had a better chance finding me behind a windshield on tour or on the computer booking tours. Back then the idea of success was an end goal – these days it is more about progress and comfort.

I signed my first record deal in 2003. Four months later, my buddies and I graduated college and tried to take our scrappy DIY indie band, Outsmarting Simon, from the basements to the big stages like we’d seen so many do before us. The early years, while still in college, started out solely as fun and they were.

We toured the East Coast on breaks and put out a demo that helped us sign with Triple Crown Records. The label gave us a couple thousand bucks and we went straight out and bought a newer van and a trailer. We’d made it!

The van broke down on the way off the lot. A trailer wheel fell off in California. We tried to scratch out a worthy existence everywhere in between.

All told, Outsmarting Simon played close to 500 shows, released an EP and two LPs, were on a decent label yet could never put more than 100 people in a room. Every time we’d get a small step up or feel like we’d reached a milestone, we’d look around and realize that not much had changed.

It always felt like the one thing we needed, the tiny missing part, was just out of our reach.

Eventually the other boys got tired of sleeping on dirty couches and surviving on cans of beans and Saltines. Considering all three of them had degrees in engineering, I couldn’t blame them. They all got jobs and I felt lost.

Next, Philly-based Marigold asked me to sing for them. We wrote some songs and things started to feel really good. There was a buzz and positive movement. Still, we exhausted every connection we had to try to sign to a good label or get on solid tours and things started to feel stagnant.

After many very fun but poorly attended tours, the band had few options and started to splinter.

As Marigold fell apart, I was offered a position as a hired bass player in The Color Fred, with ex-Taking Back Sunday/ex-Breaking Pangaea member Fred Mascherino. Fred and I knew each other from my Outsmarting Simon days and I liked the idea of joining a band with a guy from my past who’d gone on to do big things. With his talent, experience and connections, it seemed Fred could push the band to a respectable level.

I made it through two East Coast tours and a full U.S. before I got myself fired.

By the next week, I’d secured a position in a backing band for a singer on Geffen/Interscope who was managed by the company that broke Fallout Boy, Gym Class Heroes and Cobra Starship. Nine months of playing music I hated in the backing band bought me the opportunity to get paid well, sleep in hotels, tour on a bus and play to packed houses.

I did not feel successful. I felt cheap.

Every opportunity to move up the ladder felt less good. The band members were all let go that winter and four days later we’d found work with a new singer on Universal/Motown. It quickly became clear that management didn’t want to pay us properly and this fizzled out before it got off the ground.

After watching every band I was part of either fall apart, fire me or disband, I decided to try things on my own. I gave up my home and most of my belongings, stored some books and records in my friend’s basement and left.

The first year I played close to 250 shows in 12 countries, released a full length, EP and wrote part of a book chronicling it all. And it still felt so far from success.

At any point, if you had asked me what would make me feel successful, it would always be some version of “making it,” feeling like I actually had a comfortable career making music, that I was supporting myself doing the thing I loved, that people appreciated my music and wanted to hear it. But, even when I had some semblance of all of those things, it never quite felt like I did.

My older brother once asked me if perhaps my problem was not a lack of success but a misunderstanding or misapprehension of my situation. As a life, an adventure, it was the most wildly successful experience one could imagine. I’d spent the last many years traveling the world, playing music and making friends. He was right, but the problem was that I had not set out to be good at making life an adventure. I had set out to be a full-time musician.

This discord is what created the problem.

I could not see the things I had as amazing because they were not the thing I wanted in the beginning. Shifting views became important and necessary for my survival and happiness.

After about four years of touring solo and still not having a home, I began voicing more often that I may want to find a place, get off the road. I also realized I was spending less and less time working on music and spending more of my free time reading books about food, learning about craft beer.

In the spring of 2014, a great friend offered a room in his house and I decided to take him up on it. For what was supposed to be just a few months, I slept on the floor in a small room in his South Philly rowhome. That summer, I helped open the beer garden at Spruce Street Harbor Park, worked harder than I ever had and, for the first time in a long time, felt satisfied. The milestones were small but they came often and more definitively. The payoffs, literal and figurative, came quickly.

As the summer was coming to a close, I was offered a position as a barback at American Sardine Bar and so started my time behind the bar.

Working as a barback is hard and thankless but if you have a good crew, it can be incredibly rewarding. I’ve been lucky enough to work for some amazing people who have a lot to teach and I’ve tried my best to learn as much as I can from them. In my off time I read books about cocktails, craft beer and food preparation.

Every day I feel like I am progressing and sharing knowledge with others.

In my almost two years with the company, I have worked my way up from daytime barback to managing bartender and floor manager. I have learned so much and each day, I get to take care of people, give them a place to relax and feel comfortable.

It is a good feeling knowing my books and records are in one place, that when the seasons change, I don’t have to track down the appropriate clothing in a box in someone’s basement. It is nice to lay my head down on the same pillow each night, feeling like I may have made someone’s day a little better.

At home, if I feel I’ve made some progress, learned something new, then I feel successful.

At work, it doesn’t matter if I am the barback or the manager – if people are happy and if the glasses are clean, I’ve done my job.

W/N W/N: A Victory For All.

Text by Eric Fitzsimmons. Images by Grace Dickinson.

Many restaurants have adopted the language of the socially conscious. W/N W/N Coffee Bar was born in it.

Since late 2014, W/N W/N has been slinging quality roasts and teas alongside beer and cocktails at its chrome-and-glass storefront at 931 Spring Garden St. In a time when it seems every place with a food menu makes some claim to organically-grown, sustainable, grass-fed, free-range, artisanal fare, W/N W/N takes the ethical angle a step further in its community involvement and worker-cooperative ownership structure. W/N W/N is owned by the very people who work there.

Tony Montagnaro, one of the owner-workers who coordinates outreach and events, says W/N W/N came out of a group of people who had been working in hospitality jobs around Philadelphia and were tired of the way most places run.

“It’s a really exploitative industry, and most of the profits made in food and bev are due to low wage labor,” says Montagnaro, 26 , of Kensington. “Basically, those who are making all the money for the business and working the hardest have the least amount to gain, whether it be financially or in terms of equity in the business.”

W/N W/N flips that structure on its head. If you work there, you can become an owner and share in the profits and, conversely, everyone who profits is putting their time in at the bar.

Inside, W/N W/N aims more for a European-style cafe than your dimly-lit American tavern. During the summer, the sun is still up when W/N W/N opens at five on weeknights – with daytime hours on the weekend – and the place fills with light from the large front window. The tap tower shares space on the counter with the espresso machine. Display shelves behind the bar are split: liquor bottles sit on one side, mason jars of house-blend herbal teas take up the other. Art adorns the back walls and music hums along below the level of conversation. There is not a television in sight.

Behind the bar, Reddy Cyprus, 22, of South Kensington, is pulling handles. It might be the early hour or a well-cultivated persona but Cyprus comes across as the kind of guy who is psyched that you stopped in today.

Cyprus has been there since the place first opened for business and likes the open environment and having a say in the operations. Like any democratic system, it can get messy. But when everyone comes together, great things happen. Right from the start, Cyprus had a voice in how things got done.

“All of a sudden I could talk about what I wanted to see on the menu, I could talk about how a business should be run,” Cyprus says. “I’ve worked all over Philadelphia and I just feel like I’m treated like a human here, which is pretty nice.”

That openness and collaborative spirit extends to the shows W/N W/N hosts several nights each week, running from Thursday through Sunday. Montagnaro curates the events and says he is willing to work with almost anybody who writes to suggest an event. Live, acoustic music? They do that. Push the tables aside for a dance floor and bring in local DJs? They do that, too.

Austin Edward has performed at W/N W/N three times and what has set it apart, for him, is how much freedom artists are given to own the performance space. Edward, 26, of East Passyunk, most recently brought his emotional, U.K. club scene-inspired electronic music to W/N W/N, a collaboration with visuals by Hueman Garbij that he says could not have come about in other venues.

“For a place to allow myself and my friends coming in the way they have and this frequently, I don’t know any other place like that, any space where you can experiment,” Edward says. “It’s an extremely welcoming place to be as anyone — as a performer, as a patron. They extend a very warm welcome to everyone.”

W/N W/N attracts an eclectic crowd, from stragglers getting out of the big concert venues nearby to local artists brought in by the unique mix of performances and arts the bar has been highlighting through events like the monthly First Friday party, which kicks off the month-long exhibit of a local artists in the back of the cafe.

As the name suggests, W/N W/N works best when everyone benefits. Montagnaro knows nobody really thinks they will get rich off the project but the people involved hope what they do here serves as an example that other places try in Philadelphia.

“That’s been the last year and a half, just trying to figure out what works for us, what works for this neighborhood and the community,” Montagnaro says, “and how to just be a community-minded business that is actually going to affect the things that are making change in the community, as opposed to just making money and getting out.”

A Day Without Love: Finding Peace in Suffering.

Text by Joseph Juhase. Portraits by Ryan Gheraty. Show pictures by G.W. Miller III.

Brian Walker’s debut A Day Without Love LP, Solace, is a very personal project that deals with the West Oak Lane native’s experiences with depression, addiction and past relationships.

The album has two big halves, Walker states as he sits in an Old City coffee shop sipping an iced, black coffee and wearing a Kississippi shirt. The first half is about all the things that make him mad.

“I was pissed off at the punk scene,” he says. “I had lost friends. I lost my job and was unemployed, gigging to get by and doing freelance work. I was also in debt.”

He leans in before going on to describe the second half.

“I want people to know that it’s okay to be angry,” he continues. “You can find peace in the suffering that you have.”

A Day Without Love references a poem Walker wrote for a class after witnessing an incident of spousal abuse. Since 2012, A Day Without Love has been releasing content at a healthy pace, with multiple collaborators. Now, Walker is ready to take the next step with the release of the new LP.

“With the exception of one song, Solace was written in 2015,” he says. “It’s the culmination of feelings and thoughts that were buried deep inside of me.”

Jake Detwiler, who mixed and produced Solace at the now defunct Fresh Produce Studios, met Walker in the Keswick area during an open mic night. He describes Walker as a prolific writer, and Detwiler’s enthusiasm for A Day Without Love is palpable.

“I want to help people bring good records into the world,” Detwiler says of the process.

Even with Detwiler in his corner, Walker admits that recording Solace, which took place over the course of a week, was both smooth and stressful.

“People would come into the studio and say, ‘It smells like a man cave in here,’” he says. “We had been living off Chinese food and lettuce.”

Walker wrote 60 songs for the record but only 15 were ultimately chosen. Walker’s own grandmother appears on the album in a segment where she offers her view on racism.

“I was cleaning the room with my grandmother.” Walker shares. “We had talked for about 12 to 16 minutes. She started going on about different things in her life and I just turned on the recorder. If you listen, you can hear the air conditioning in the background.”

Bringing people together through music has always fascinated Walker. When A Day Without Love played SXSW, things began to fall into place.

“I went in expecting barbeque and rock and roll and instead had a rebirth,” Walker recalls. “It didn’t feel like a competition between musicians. I really felt the camaraderie from other artists of different genres.”

Walker is no stranger to camaraderie, as he frequently interacts with fans on social media. He often shares his own experiences – the good, the bad, the difficult. Living with depression, Walker is very vocal about sharing his experiences with others. He frequently hands out information about Erika’s Lighthouse, an organization that aims to educate communities about teen depression, at his shows.

And with the new LP, Walker aims to speak about himself while talking to others.

“I wanted people to act on treating each other better,” Walker explains. “I want Solace to be selfless, keep pain alive and give more than take.”

Prinze George and Julietta @ Johnny Brenda’s.

Text by Chris Zakorchemny. Images by Grace Dickinson.

Text by Chris Zakorchemny. Images by Grace Dickinson.

As man-buns and boutique fashion sense became an unspoken theme of the night at Johnny Brenda’s, it felt like a synthesis of the cultural shift that has been underway in Fishtown. As the venue/bar prepares to celebrate their 10th anniversary, it still stands as a bastion to an area that is seemingly losing and gaining it’s identity at once.

Similarly at a crossroads is the allure of romantic synth-pop bands in the same vein of the Drive soundtrack. Johnny Brenda’s hosted two of those bands: Brooklyn-based Julietta and Prinze George (above). Both produce music that could easily serve as montage music for long, beautiful shots of Ryan Gosling’s face as he stares down the streets of L.A. But when the very song that probably sparked a genre moment is in a Chrysler ad with Jim Gaffigan, it’s usually a signal that what is commercially acceptable can now be replicated with ease.

The challenge these bands face – just by virtue of playing non-aggressive synth-driven music – is to push a boundary with pretty clear markers. Clear enough for Chrysler and clear enough to ignore in the background.

Julietta are more the R&B side of head-nodding synth pop that Wet have explored, and hearing “Conquest” in person sounded every bit the breakout hit it’s worth being. Even as a four-piece, their sound came across just as full as Prinze George, who used a backing track throughout their set. Although Julietta’s sound rarely veered outside of the realm of a pulsing ballad (save for their inspired cover of Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black”), they did seem to hit stride later in their set on “Nightmare,” which alternates between hums of synths and high piano notes.

By the end of the set, a good number of the crowd had created a semi-circle around the stage, perhaps five steps back. It was almost as if everyone agreed they were entranced enough to take in the music but not enough to get really close to it.

When Prinze George took the stage, the crowd inched closer. Their hits “Upswing” and “Victor” drew woos and smooth body sways from the crowd, but every time they presented something that didn’t seem to flow on a consistent beat, the crowd seemed to grow more enthusiastic.

During the second half of their set, “Move It” stood out, if just that for the first minute, there were no drums. Similarly, “Lights Burn Out” felt a bit “Trancendentalism” by Death Cab for Cutie for how stripped down and emotional the words were (now that you could hear them clearly).

When called for an encore, the trio returned to the stage with “Windows,” another song bared down to it’s essentials. Without a backing track it almost felt impromptu, and a step above the tracks draped in overabundant production.

Both bands beckon the question that if you dress up a song to sound pretty, does the song at it’s core still hold up as something worth your attention? Both bands answered the call.

Larry Magid: The Scene Builder.

Text by Tyler Horst. Images by Charles Shan Cerrone.

Text by Tyler Horst. Images by Charles Shan Cerrone.

Larry Magid remembers when there was no rock ‘n’ roll in the city.

“Nothing happened in Philadelphia,” Magid says. “There was no scene.”

Long before Union Transfer and Underground Arts, before stadiums like the Wells Fargo Center would even think about holding concerts and before Ben Franklin smiled from the roof of the Electric Factory, Philadelphia was mostly a jazz town. In the early 1960s, a young Magid was just getting his feet wet in the music industry. Over the course of the next half-century, the West Philadelphia native would become responsible for many of the city’s most historic music memories.

“You just ride the wave,” Magid says with a shrug, reflecting on the towering list of acts he helped bring to Philadelphia, from Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix to the international phenomenon of the Live Aid and Live 8 concert events.

Sitting inside a spare conference room of the modest offices of his company, Larry Magid Entertainment, the man whose name is on the door is dressed as unassumingly as his attitude in a simple button-down shirt and thick-rimmed glasses.

Plaques and guitars are stacked in corners, waiting to decorate the walls but the work always comes first. Magid doesn’t need to prove himself to anybody at this point. Now 73, Magid still isn’t ready for his career to be considered a retrospective. The music mogul takes a break from another hectic day. He’s just got off the phone with London, and he has an appointment to keep with Bruce Springsteen’s people later in the afternoon.

The music business was not Magid’s first intention.

Magid studied communications at Temple University in the 1960s. Hoping to become a writer, he worked for a small music publication run by a friend. One afternoon, someone in the office asked Magid to book bands for a fraternity party at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I said I would do it, then I had to figure out how I would do it,” he recalls with a laugh. “And it worked.”

The new career path stuck.

Magid never finished his degree. He left for New York City to work for a booking agency and learn the ropes of the music business before his hometown started tugging him back.

When visiting home, Magid liked to spend time at the Showboat, a jazz club that was run by the Spivak brothers: Allen, Jerry and Herb. The Spivaks knew Magid was a talented booker, and one day in the late ’60s, they pulled him aside for advice. Magid says the Spivak brothers saw what was happening in the rest of the country and wanted to get in on the rock business here in Philadelphia. Magid’s advice?

“You have to start building things.”

Soon after, out of the shell of an old tire warehouse on 22nd and Arch streets, the Electric Factory was built, and Magid was the one chosen to fill it.

The original Factory held 2,500 people, far beyond what any other venue in Philadelphia could handle at the time. It opened in 1968 with a concert by psychedelic soul act the Chambers Brothers. It was just in time for a period that many remember as a counter-cultural revolution, and the artists that supplied its soundtrack could be found night after night at the Electric Factory – Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Frank Zappa, the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd and the list goes on. Fans saw the greatest talent of their generation with tickets costing only $3 per show, courtesy of Magid.

Some of Philly’s own got to take the stage as well, like renowned musician and producer Larry Gold, who played the Electric Factory many times with Michael Bacon as the band The Good News.

“It changed the core of the city,” Gold says about the Electric Factory’s cultural impact. According to Gold, the music and culture of the day was already present in the city, but the Factory provided a place for it to come together and be amplified. Nobody else was bringing the music quite like Magid.

“Larry [Magid] is one of the people who invented the rock ‘n’ roll business,” says Bryan Dilworth, co-founder of Bonfire Booking and a talent buyer for the Electric Factory. Dilworth worked for Magid for several years when the Electric Factory re-opened at its current location on 7th Street near Callowhill.

“The procedures, the way we market things, all the way down to the way we present shows—he had to come up with all of that,” says Dilworth.

In 1985, Magid helped bring Philadelphia to the world stage through Live Aid, the historic benefit concert held simultaneously in England and the United States. Magid’s friend and veteran promoter Bill Graham was asked to spearhead the organization of the U.S. portion and told Magid he was thinking about doing it in New York City.

But Magid could think of no better location than Philadelphia’s own JFK Stadium, the former open-air sports stadium in South Philly.

Magid was tapped again 20 years later when he was 63 to organize Live 8 (pictured above). Many people might have taken such a massive moment in their career as a good note on which to retire, but Magid isn’t like most people.

Magid has experienced his fair share of changes in this latter half of his career. Though he still owns the Electric Factory venue, he sold his company, Electric Factory Concerts, to SFX Entertainment in 2000. SFX was acquired by the Clear Channel Entertainment division, which later became Live Nation. An empire was building, and Magid had a view from the top as a chairman.

But his heart wasn’t in it.

“Clear Channel was a prison sentence,” Magid says. “I used to joke that I was the Count of Monte Cristo, counting off the days in my cave with chalk marks until I was free.”

Selling his company meant the promise of job security for Magid’s many employees, but it also meant a contract. What Magid realized was that he didn’t want to be somebody else’s employee.

So in 2010, at the young age of 67, Magid decided to strike out on his own.

“You start over again,” he says about his decision. “But you don’t have to start from scratch, and you don’t have to do what other people want you to do.”

Since leaving Live Nation and starting Larry Magid Entertainment, Magid has been much happier. Rather than working 12-hour days and dealing with hundreds of concerts per year, like he did at his old job, Magid is now able to be more hands-on with a few heritage acts he’s grown close to over the years, like Billy Crystal and Bruce Springsteen.

“Nothing could make me prouder than watching Bruce Springsteen, who started as an opening act, become the biggest act in the world and knowing that I was a part of the catalytic force that enabled that creativity to grow,” he says.

These are the parts of his work that stick with him—watching Crystal go from a club comic to a comedy legend, or putting on a concert for Billy Joel before he had put out his first record.

“It’s like a doctor bringing a baby to life,” he says.

Seeing the potential in an act is what Magid believes set him and his team apart. When Magid caught a glimpse of the future in an act, he did everything in his power to make his premonition come true.

“We weren’t just working on that one show, we were also working on the next show,” he says about putting together concerts for promising acts.

“We were building something.”

More than just building world-famous entertainers, Larry Magid was building Philadelphia into the music city it is today.

Text by Tyler Horst. Images by Charles Shan Cerrone.

There is barely enough room for Michael Fichman to sit down in the recording studio he built in his West Philly home. He slides between two guitar stands and sits down in front of his desk, atop which sits a computer and huge speakers pointing back toward shelves upon shelves of his dense record collection. Then he queues up a track off his upcoming album.

“Generally speaking, this is not what’s popping in the club scene,” Fichman says with a laugh.

While that may be true of the club scene in general, here in Philly, people get it.

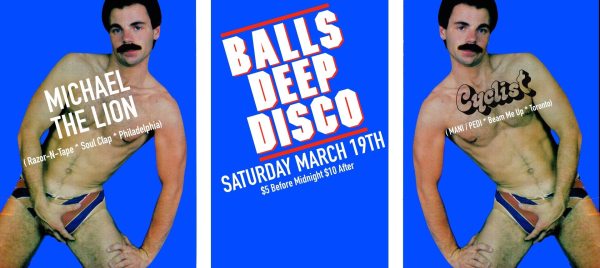

That’s because Fichman, who goes by the stage name Michael The Lion, samples heavily from the types of disco, funk and soul music that have deep roots in this city. It’s also got him huge recognition at clubs like Franky Bradley’s, where people are looking to get down to something a little funkier.

When Fichman started DJing at Taylor Allderdice High School in Pittsburgh (the same school as Wiz Khalifa and Mac Miller), the now 33-year-old DJ went by the name DJ Apt One.

“That name meant I could play anything at any time,” he says.

After moving to Philadelphia in 2001, Fichman’s first claim to fame was a party he dubbed Philadelphyinz to connect his new home to the “yinzers” of his birthplace. It was an exciting time to be a DJ, Fichman says. Especially in Philadelphia.

“You could play anything at any time and mix broad styles together. And Philly was exporting it,” Fichman explains. “Cosmo Baker, Rich Medina, Diplo—these guys were taking this around the world and I was fortunate to kind of get in under the bar when people in other cities wanted to hear what people in Philly were doing.”

Fichman had monthly gigs at Medusa Lounge and Silk City, where he’d mix Baltimore club music with Chicago juke and everything in between. In his private studio time though, Fichman was becoming increasingly interested in the sounds of yore.

“I started playing hip-hop, so I learned about music in reverse by finding the samples in the songs that I liked,” Fichman says of his gravitation toward funk, soul and disco.

As Fichman’s secret catalog grew, it was his friend and fellow DJ Cosmo Baker who gave him the push to pursue production.

“Cosmo Baker, who’s a friend of mine and one of the people whose opinions I respect the most, said, ‘This is really amazing. You need to create a new side project for this, or change the name,’” says Fichman.

“There’s a certain soulfulness that has been lost in dance music,” says Baker, who recently opened the Philly branch of Scratch Academy. “I appreciate the way he pays homage to what came before without sounding cheesy or retro.”

With encouragement from Baker, Fichman set about devising a new alias and ended up going with his own name. Aryeh, Fichman’s middle name, is Hebrew for lion.

“I had been trying for years to access a new level,” Fichman says.

With the new direction, he was able to get there. Music that he had been working on in private suddenly found new life. Soul Clap Records ended up putting out Fichman’s new music on vinyl in 2014.

“What was old to me became new to everyone else,” he says about bringing out his Michael the Lion music for the first time.

Fichman’s first set as Michael the Lion was at the first installment of his Hooked party at Franky Bradley’s in March of 2015 and it set the bar record for total profit from sales in one night.

Seeing how pleased the packed crowd was with Fichman’s music, Franky Bradley’s insisted he bring the Hooked party back to the venue every month.

“I looked around and said, ‘I think we’ll do it every quarter. We don’t want to wear this out,’” Fichman says.

Fichman’s proudest moment was when a DJ from New York contacted him on Soundcloud about a 40th Anniversary box set for Philadelphia International Records. To his starstruck bewilderment, Fichman learned that the legendary Kenny Gamble wanted to buy his Teddy Pendergrass remix for the record.

He was the only Philadelphia artist to do a remix for the box set.

It’s no surprise Fichman has found success with the sounds of funk and disco because really, he says, they’re Philadelphia’s sounds.

“People in Philadelphia fundamentally appreciate it,” he says. “It’s a part of our culture.”

Red Martina: A Cool Mosaic of Sound.

Text by Hanna Kubik. Images by Magdalena Papaioannou.

The chemistry between two or more people is sometimes instantaneous and undeniable. Once formed, these bonds are hard to break. For Haley Cass of Red Martina, this moment came when she created music for the first time with bandmates Ish Quintero and Ben Polinsky.

“We wrote the hook of our first song outside the first day we all met,” says Cass. “We knew it at that moment.”

Before Red Martina became a seven-member band creating music in a West Philadelphia basement, they started off as a foursome. Quintero, the group’s multi-instrumentalist who decides what they’re going to sample, was working on hip-hop and trip-hop projects with Stoupe, a local Philadelphia producer. Once Polinsky and Cass were invited on as vocalists, the sound and rhythms to Quintero and Stoupe’s previous projects became more diverse. Red Martina was born.

“When Haley and Ben came to start working with us, we realized we could use what we had in different ways,” says Quintero. “We didn’t have to stick to the formula of a rap song where Ben would rap and Haley would do the hook or chorus.”

Their ability to stray from any set formula was amplified after the additional members, Noam Szwegold, Adam Williams and Aaron Blouin joined the group. Drawing on various musical influences like Parliament Funkadelic, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Caribbean and Latin rhythms and Billie Holiday, Red Martina’s songs blend elements from a broad range of genres. To categorize them as pure hip-hop would be ignoring the richness and complexity of their sound.

“What makes a good band is the sum of its parts and since we all come from different backgrounds, it’s kind of like a creative tension in a good way because it creates a unique sound,” says Szwergold, the band’s pianist. “The songs are versatile, and I think that’s reflective of the Philadelphia music scene. There are so many backgrounds and genres that come together and make this cool mosaic of sound.”

This mix of sound and their ability to bring it all together in a cohesive, head-nodding way, forces the audience to truly listen during Red Martina performances says Cass.

“It’s not just young kids or one type of person,” she says of the band’s fan. “We get people who really want to listen to music, who are not there to party, but to listen to what we have to play,”

Fans have flown from Chicago and Denver to listen to their live performances, which they have started recording as a tribute to their followers, both in the States and abroad.

“They had their first show at Milkboy in Philadelphia and I was utterly impressed with their performance, especially it being their first one,” says Taylor Gannon, a fan of the band since their early days as a foursome. “More people in Philadelphia should get a chance to listen and see them live.”

Gannon adds that the band’s complexity in being rooted in hip-hop, jazz, funk and even reggae is what makes them all the more interesting.

“With all of the new music coming out these days, even just in Philadelphia, it’s nice to hear something straight up different from the rest,” she says.

To get lyrical inspiration, Polinsky says he does not look much farther than his own home of Philadelphia. Whether it is taking a walk around the streets to clear his head or hopping a ride on SEPTA, the stories are all around him.

“It’s like Mr. Cheeks from Lost Boyz says, ‘Sometimes I take the train just to clear the brain,’ and I think it’s really true,” says Polinsky. “It’s tough to write if you don’t get out to see what people are doing.”

While Red Martina is working on their next album, they have not set a release date yet.

“We will release it when the moment is right and we feel good about what we’re putting out there,” says Cass. “For music that draws from so many people and tastes, we can’t rush.”

In protest of having that album, or any of their other work boxed into one genre again, Red Martina created their own. They call it West Philly Basement.

“It’s where we make our music and it embodies who we are, where we’ve come as a group and where we still can go,” says Szwegold.

Red Bull Thre3Style US Finals @ Union Transfer.

Text and video by Donte Kirby. Images by Dave Rosenblum.

Last Thursday night, at Union Transfer, six turntablists mixed, scratched and spun with all they had for 15 minutes each to determine the United States champion in the Thre3Style competition, Red Bull’s search for the world’s best DJ.

The legendary DJ Jazzy Jeff, renowned turntable champion Skratch Bastid and 2015’s world Thre3Style winner DJ Byte served as judges for the night, critiquing contestants on versatility, originality, technicality and stage presence.

To see this many world-class DJs in one night, most people have to travel to a major festival like EDC and even then, the music doesn’t always skirt as many genres per DJ as Thre3Style prides itself on. To have Journey mixed with Jay-Z melded into Don Omar is a transformative experience for the hips. With DJ Royale and Matthew Law warming up the crowd, along with the judges hitting the decks after the competition, the audience would be shepherded on a musical journey by 11 different DJs.

Atlanta’s DJ Jaycee opened the competition and delivered a mesmerizing scratching finale. Chicago’s Boi Jeanius performed next and delivered a charismatic set highlighting his Chi-town roots and paying homage to DJ Timbuck2, who passed last year after a battle with cancer. In the third slot, Las Vegas representer DJ Ease’s set had the crowd knucking and bucking one minute and frozen in awe at his mixing the next. Minneapolis native DJ Mike 2600 dazzled with the beat machine and Guam’s (by way of Seattle) DJ Supagi sonically controlled the crowd with his song selection and beat creation.

But it proved to be a night of vindication for longtime Thre3style competitor, DJ Trayze, who was and the last to take the stage. Performing a set he had worked on for six months, he was he was crowned the champion and will serve as the North American representative for the Thre3Style World Finals in Chile this December.

As the other competitors threw shots at each other during their sets, Trayze was bulletproof. When Boi Jeanius played the snippet from “Half Baked” where Scarface quits his job and flipped off all the other DJs, Trayze was cool. When Supagi showcased his bravado with a mix involving the competitor’s drops and MC Hammer’s “Can’t Touch This,” he was quick to add, “Trayze, you can touch this.” The good natured shots and excitement of battle culminated in hugs all around when Trayze received the title as United States’ 2016 Thre3Style Champion. Boi Jeanius took second place and jaycee came in third.

But the night was not over.

After the competition, DJ Byte showed his mix mastery and why he was crowned 2015 Thre3Style champion with a set that often had the night’s competitors lined up and on the side of the stage amazed. Towards the end of Byte’s set, his turntables had some issues but like a professional, he soldiered through until it was time to take a bow. DJ Jazzy Jeff and Skratch Bastid performed simultaneously on two sets of turntables, with a back and forth that showcased their chemistry and abilities. Even a few legendary DJs like Z-Trip took a turn or two on the tables before the clock struck 2 a.m.

By the end of the night, those who walked out of Union Transfer’s doors couldn’t say they hadn’t been treated to six hours of genre bending mixing, scratching and spinning.